We have a bundle of volunteer cherry tomato plants in a planter just outside our back deck. My partner buys those containers of little cherry tomatoes, and occasionally there will be a little soft one that gets tossed out into the yard. Turns out they sprout rather easily, and so now we have these sprawling, unruly plants giving us new tomatoes all summer. It’s delightful and seems like a magic trick to me.

Anyway, a couple of weeks ago I noticed these big fat catepillars on the tomato stalks. They are so well camoflauged, their chunky little bodies so perfectly shaded green. I don’t know how long they’ve been there, and I wonder how many times I must have missed them when I went out to pick tomatoes. On this particular evening, I think what actually caught my attention was the little white spots. I was out watching bats, and it was almost dark out, so the bright white stood out against the darker green of the plants.

What on earth are these things?

We didn’t really get a very good look that first night, but we did our best to get some photos. We counted four catepillars, in varying sizes, all with these masses of little white sacs attached to their backs.

I went out again the next day, of course, to get a better look. Look at those grippy little feet! The little eye spots! Those bold stripes! That spiky little butt!

Some digging around on the good old interwebs tells me this is a tobacco hornworm, festively adorned with the cocoons of a braconid wasp. (There is another very similar variety of hornworm, called the tomato hornworm, that has slightly different striping and a different colored spike on its butt)

Here’s how it goes, apparently. The moth, common name Carolina sphinx moth, or tobacco hawk moth (manduca sexta), lays its eggs on the plants, and they hatch into these big fat catepillars. (Obviously this is simplified - THIS wikipedia article has some really interesting information about the manduca sexta, including the fact that the hornworm’s heart becomes visible through its skin during the last larval stage) The braconid wasp lays its eggs IN THE BODY OF THE HORNWORM, and the wasp larvae feed on the hornworms’ guts. The wasp transmits a virus which disables the hornworm’s immune response, thereby preventing it from killing the wasp larvae. The wasp larvae then BURST OUT of the body of the hornworm and build themselves those cocoons right on the hornworm’s back. The hornworm remains alive and will continue to feed, although at a much reduced rate.

After about 4 days, the grown wasps cut themselves a little escape hatch in the cocoon and emerge, and start the process all over again.

I was able to witness some of the tiny wasps emerging from their cocoons (alas, I didn’t capture a video) and it was captivating. The morning before they emerged, I noticed that the cocoons looked darker in color.

I watched this process play out on all four hornworms over a couple of days. To my astonishment, after watching some wasps hatching one morning, I went out later that afternoon and saw some new larvae emerging from the same hornworm. They immediately starting spinning cocoons.

How fascinating is this??

The hornworms didn’t live much longer after this process, but I don’t know what’s typical, and I can’t be sure that what I saw was actually the first “round” of hatching. I wonder if there’s variability in the number of times each hornworm can support a new round of wasps.

I also noticed that the hornworms themselves were generally pretty slow to repond to being disturbed, and moved and ate pretty slowly too. Also interesting to me was the observation that they would kind of curl their heads back or under if I disturbed the stalk they were on, but they didn’t do that if the stalk moved in the wind. I’m interested to see how quickly they would move, or how different their behaviour might be when they’re not playing host to all these parasitic wasps.

The hornworms are widely considered pests, because apparently they are big eaters, and just a few can quickly decimate an entire crop. The parasitic braconid wasp is a natural control, and an “infested” hornworm will eat much, much less than its unencumbered counterpart.

I’d really love to catch a glimpse of the moth version of these creatures, as apparently they can be pretty large.

I’d really recommend diving into that Wikipedia article linked above, because there’s a lot of interesting information in there. I haven’t done much of a deep-dive on the braconid wasp yet, but that’s on my to-do list.

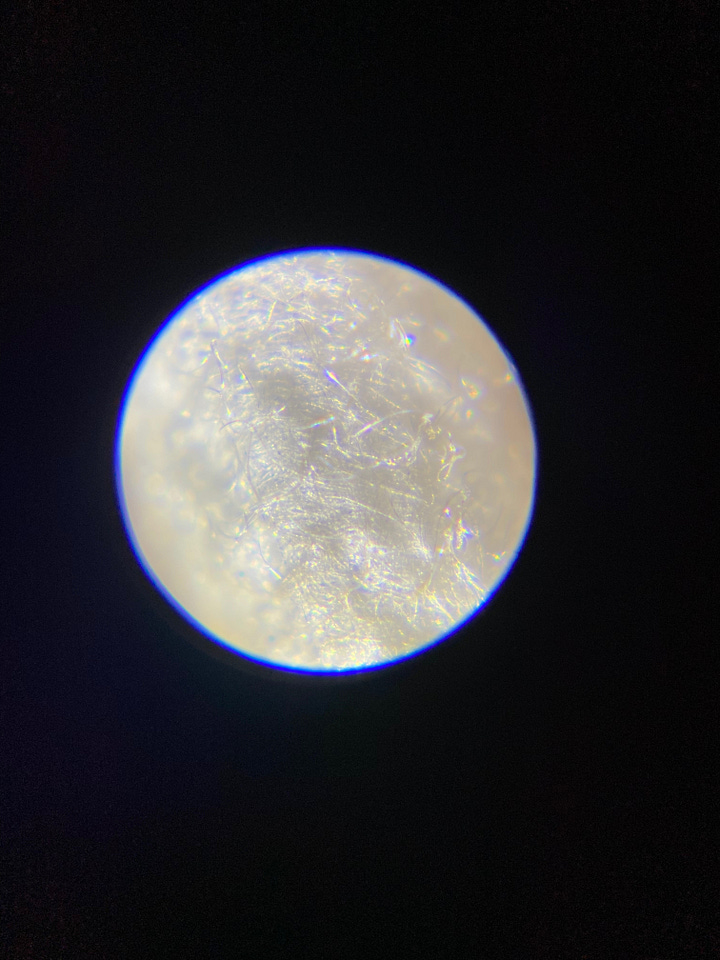

I collected a bunch of the empty cocoons to add to my collection of Interesting Things. Before they went into the vial though, I studied them with the mini-microscope. The structure of the cocoons is pretty amazing, and they’re very tough. The filaments are glossy looking under magnification, and the layers remind me of fiberglass.

I wonder if the cocoons will break down over time? What are the fibers made from? Are the wasps capable of reproduction immediately after hatching? Do they have stingers? Do the adult wasps eat, or do they live only briefly for reproduction? Do the adult wasps have any natural predators? I’m looking forward to learning more about these creatures, because I’m sure there’s much more that wouldn’t even occur to me to ask.

That’s all for now. Thanks for reading!